territory, cows, and the crooked paths to policing’s autocracy

"the conquest of rural space was an important step in the development of the police power necessary for our age of mass incarceration and ungovernable law enforcement."

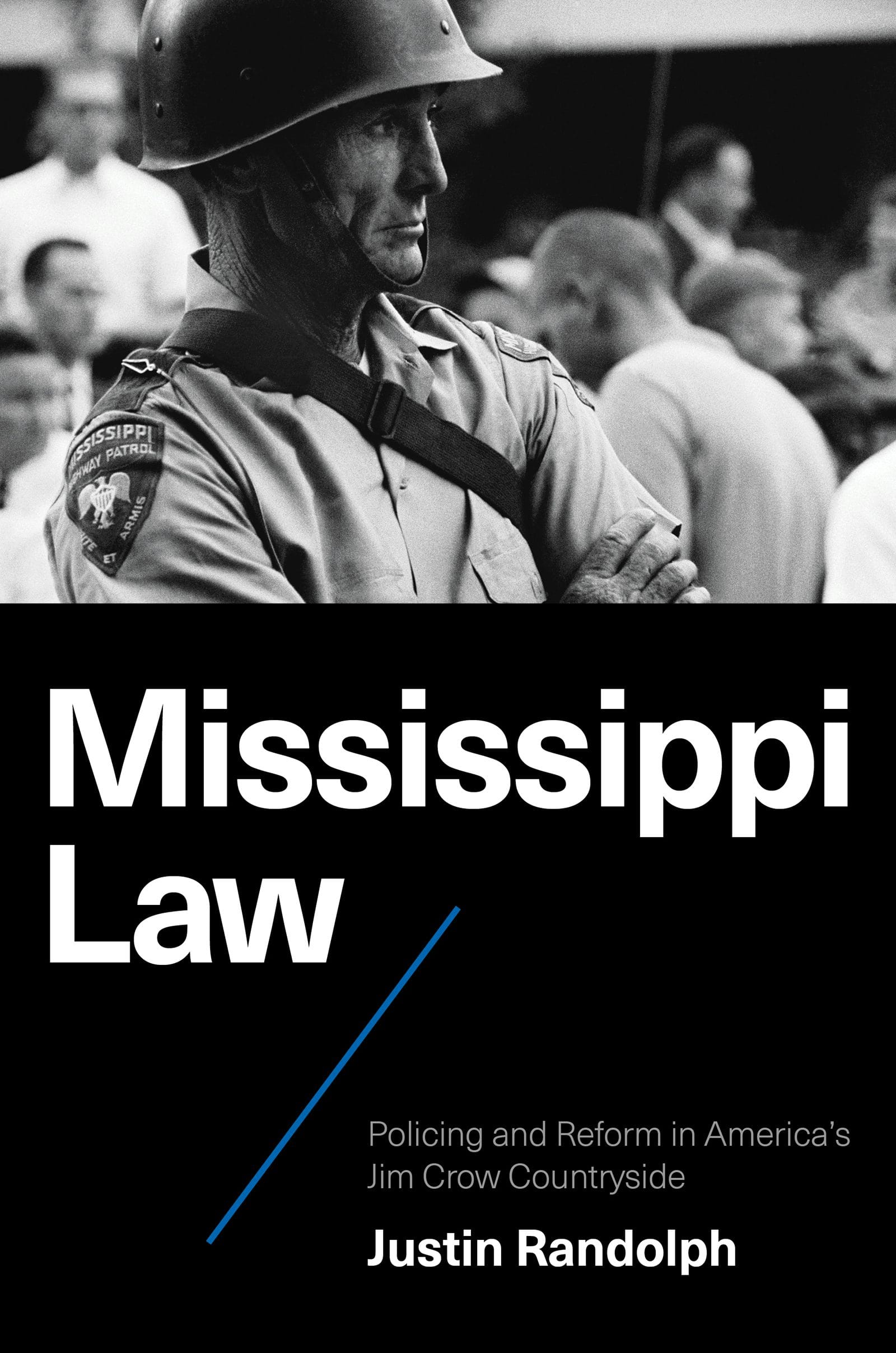

today's author's pitch comes from Justin Randolph, an assistant professor of history at Texas A&M and author of a must-read new book from UNC Press, Mississippi Law: Policing and Reform in America’s Jim Crow Countryside.

One morning in summer 1964, A. C. Whitaker fought for his life. The night before, the Black civil rights worker had caught a flat tire in rural Sharkey County, Mississippi. Whitaker didn’t think much of it. He locked his car doors and hitchhiked to the nearest town for tools. The next day, he returned to where he left his car, but it had vanished. Whitaker asked a highway patrolman parked on the side of the road if he had seen his car. The white officer said he had ordered a garage to tow it and offered to take Whitaker there. Once in the garage manager’s office, the trooper bolted the door and attacked the activist with his truncheon. “He asked me why I locked my car ‘in his territory,’” Whitaker remembered in a statement to US District Court. He grabbed the trooper’s blackjack, midair. “I told him that he could kill me before I’d turn it loose.” The officer left him with a threat: “Get your black ass out of Sharkey County,” he said. “Don’t be caught here no more.”

We might ignore the trooper’s reference to his territory as bluster. But the idea of space and land belonging to a ruling class and its lawmen had deep ties to the force required to conquer and exploit the earth. It impacted the way civil rights workers like Whitaker moved through the world in Freedom Summer 1964, and its vestiges remain with us today, in redevelopment and gentrification far beyond Sharkey County. I tell Whitaker’s story in Chapter Eight of my new book, Mississippi Law: Policing and Reform in America’s Jim Crow Countryside, where I show that the conquest of rural space was an important step in the development of the police power necessary for our age of mass incarceration and ungovernable law enforcement.

At the dawn of Jim Crow, a military-police form emerged from Gilded Age anxieties over desperados and labor radicalism. In 1890, lawmakers formalized notorious parts of Jim Crow in a new state constitution, including school segregation and voter disfranchisement. They also recommended a massive new investment in paramilitary power to police “the two races which now occupy our territory.” The state militia (state troops) gave way to the National Guard and eventually the state police (state troopers). I call this evolution paramilitary police reform and emphasize the emergence of Mississippi’s state police force, a highway patrol, to show how state policymakers with unique affinities with racial liberalism shaped law enforcement for inequality after racial apartheid.

When the book ends, state troopers hit the streets of Jackson, the state’s urban center. In 1965 they locked protesters in a cattle barn stockade at the state fairgrounds. And in May 1970, just days after the Kent State massacre, troopers shot military grade weaponry into a crowd of protesting students at Jackson State College, killing two Black men and wounding many other men and women. How did state troopers assigned to state highways end up brutalizing and killing people on city sidewalks?

The troopers’ use of a cattle barn as a makeshift camp in 1965 offered one clue. Cows were an important part of this historical puzzle. In Mississippi, cotton was king, but beginning in the 1930s, the state’s rural economy began to rapidly diversify. One way to understand this diversification is to appreciate the transition from labor-intensive to land-intensive agriculture, from cotton planted and picked by Black hands to more mechanized crops like soy, timber, and catfish. Beef was another land-intensive economy. Unlike these other sectors, beef cattle inspired its own small state police force to secure bovine capital, the Mississippi Livestock Theft Bureau (1950). And unlike other parts of the state police, these Investigators had jurisdiction to investigate cattle thefts anywhere in the state—not just on highways. They wreaked havoc. Just 7 inspectors arrested over 1,400 people in the Bureau’s first decade, averaging 12 arrests per month.

More than scale, the legal precedent and white approval for this policing mattered. The state’s Black freedom struggles coalesced into a full revolt in the 1960s, and in March 1964 white lawmakers increased the state police by two hundred new white officers and granted the Livestock Theft Bureau’s general police powers to all investigators in the highway patrol. These men disrupted the civil rights movement frequently. In the words of the governor at the time, “Hades is not hot compared to what we want it to be for some of these people.” The same governor promised to pardon any trooper convicted by a court for their conduct against activists.

A. C. Whitaker experienced the intentionally ungovernable police violence that tied his experience to past and future struggles for Black freedom on territory claimed by white elites. I call this rule based on disorder policing’s autocracy and hope more scholars will attend to the historic ties between political economy, force, and reform that yield systems of inequality in a given historical moment.

Mississippi Law: Policing and Reform in America’s Jim Crow Countryside

Carceral History is an always free newsletter published as a professional service by a historian and working mom who's watching a lot of Blue's Clues these days.

Want to contribute? Email carceralhistory@gmail.com.